How screen time and coffee disrupt your sleep

We are living in what is described as the golden age of sleep science.

In the last 100 years, humans have gone from questioning the very reason for sleep to understanding that no function of the human body is spared the crippling, noxious harm of sleep loss [1].

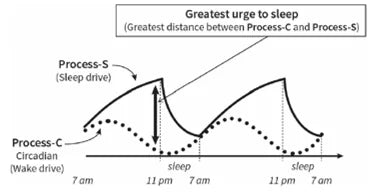

We also now have a better understanding of what goes into producing sleep in our body, owing to a framework called the Two-Process Model first described by Alexander Borbely in a landmark 1982 research paper [2]. This paper explains the two processes that come together to produce sleep in our body.

The first process is the Circadian Process – the cycle of day and night.

1. The Circadian Process

Humans are a diurnal species – waking at daytime, sleeping at night.

To sync our sleeping times with night, our brain has evolved an elaborate mechanism called the Circadian drive, which helps to keep our bodily rhythms in rhythm with the rising and setting sun.

Simply put, when the sun’s light is not entering our eyes, our brain produces the hormone Melatonin. Specifically, our brain has a timekeeper called the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus (SCN), which, in the absence of sunlight, signals the Pineal gland to begin Melatonin production.

Melatonin is our hormone of darkness – it turns down our Circadian Wake Drive. It signals downtime to the body, telling it to make corresponding adaptations. The heart rate, blood pressure and body temperature all reduce under the influence of Melatonin.

Melatonin tells the body that it is now time to sleep. Specifically, it turns down our Circadian wake drive.

Normal Melatonin production is critical to our ability to produce sleep.

In certain populations such as people over 55 years of age, those with jet lag or irregular / unusual sleeping hours (shift workers, new parents or other caregivers), enough Melatonin is not produced at sleeping time, which is when supplementation may be helpful. More on this later.

Even through closed eyelids, the bright morning light stops the production of Melatonin, closing our ideal window of time for sleeping. Those of us who “simply cannot sleep beyond a certain time in the morning” may take note.

Now our brain is wired to recognise blue light as the bright blue sky. Naturally, blue light at hours when it is not supposed to exist can effectively stop our Melatonin production, thereby preventing sleep.

This is where screen time comes in.

Through the bright blue light that they emit, electronic screens trick the brain into thinking it is daytime [4]. Naturally, scrolling on a phone screen or being hooked on a laptop screen “simply because I can’t fall asleep” is a vicious cycle of counterproductivity – the screen isn’t just helping you kill time till sleep comes; it’s actively preventing you from falling sleep.

Now avoiding screen would naturally be the most obvious, effective solution. If you’re not able to do so, though, changing the screen to ‘Night mode’ or a ‘Soft’ colour screen changes the colour balance to warmer colours and less blues, or using blue light filtering / yellow tinted glasses [5]. Using these strategies, one can safeguard their sleep from disruption.

Melatonin, however, is not sufficient to produce sleep – a second process is also necessary. This is the Homeostatic Process – the process of tiredness and sleep pressure.

2. The Homeostatic Process

Now as you may know, our bodies use energy throughout the day.

You may remember from Biology class that energy is stored in the cells of our body as a molecule called Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP).

As ATP releases energy in the body, it breaks down into a molecule called Adenosine.

Adenosine is, thus, literally the currency of tiredness in humans.

As we keep spending energy through the day, we keep collecting Adenosine in our body. Our brain has receptors for Adenosine, which signal our ‘degree of tiredness’.

Now Adenosine is itself a powerful sedative – the more tired we get, the more sleepy we feel. This is also why we sleep better on days when we exercise (with some caveats – more on this later).

Adenosine, however, also turns down our wakefulness hormones – Cortisol, Adrenaline, Histamine, Serotonin and others.

Thus, through multiple pathways, Adenosine helps start and sustain sleep in our body.

Our body’s energy and tiredness cycle

The collection of Adenosine in the day is reversed during deep sleep. This is when Adenosine clears from our brain – by being converted back into Adenosine Triphosphate and other metabolites – helping us wake up feeling refreshed and energetic [6].

This is the balance (homeostasis) that the body cycles through in one day of waking and sleeping.

And this is where coffee comes in – it is simply the commonest Adenosine disruptor humans use.

Caffeine from coffee preferentially attaches to Adenosine receptors in our brain, effectively blocking Adenosine. Since Adenosine is how we feel tired, caffeine makes us ‘not feel our tiredness’ for some time. This gives us the short boost of energy and focus we usually associate with coffee, but, as you can imagine, this also reduces the sleep pressure we feel.

Having coffee in your system at bedtime, thus, disrupts our sleep. For this reason, Matt Walker – one of the leading leading sleep scientists of our times call coffee “the most widely abused legal drug in the world”. Moderation, therefore, is called for.

One of the most critical aspects of moderating coffee is use having a hard stop of consuming coffee at least 5-7 hours before sleep. We will write in much more detail on coffee usage in future articles, with the aim of giving you all the information you need to get fantastic sleep day in, day out – do make sure to subscribe to our newsletter.

Summing up

This, therefore, is the story of sleep production – the Circadian drive makes sure we have enough Melatonin in our system at bedtime, and The Homeostatic process makes sure we have enough sleep pressure through the accumulation of Adenosine. Through the combination of these, we produce healthy, relaxing, satisfying sleep night after night. Moderating our use of disruptors like screen time and coffee helps us ensure this.

Since Borbely’s landmark findings, we have unearthed another couple of factors that are ‘permissive’ for the production of sleep – perhaps less commonly disrupted, but equally necessary. More on this later.

For now, sleep well!

References

[1] Why We Sleep

[2] The Two-Process Model of Sleep – A Reappraisal

[4] The influence of blue light on sleep performance and wellbeing in young adults: A systematic review